Like the Rhus vernix, described in our first volume, this plant is regarded with aversion, and too frequently furnishes cause to be remembered by persons of susceptible constitution, who unwarily become exposed to its poisonous influence. The general recognition of its deleterious character is evinced in the application of the names Poison vine, Poison creeper, and Poison Ivy, which are given to it in all parts of the United States.

Like the Rhus vernix, described in our first volume, this plant is regarded with aversion, and too frequently furnishes cause to be remembered by persons of susceptible constitution, who unwarily become exposed to its poisonous influence. The general recognition of its deleterious character is evinced in the application of the names Poison vine, Poison creeper, and Poison Ivy, which are given to it in all parts of the United States.

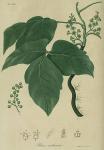

The Rhus radicans is a pretty common inhabitant of the borders of fields and of woods in most soils which are not very wet. Its mode of growth is much like that of the common creeper, the Ampelopsis quinquefolia of Michaux; and like that vine, and the European Ivy, it would doubtless be cultivated for ornament, were it harmless as it is handsome. As its name implies, this vine ascends upon tall objects in its neighbourhood by means of strong lateral rooting fibres, which project in great numbers from its sides, and attach themselves to the bark of trees and the surface of stones. The extreme branches of these fibres appear very strong in proportion to their fineness, and insinuate themselves into the minutest pores and crevices. The adhesion of the vine to the bark of trees is frequently so strong, that it cannot be torn off without breaking, and I have repeatedly seen large stems of the Rhus completely buried in the trunks of old trees, the bark having grown over and enveloped them. The fibres are analogous in their structure to fine roots, and consist of a regular wood and bark. They are sometimes thrown out in such numbers on all sides, as to give the vine a shaggy appearance and conceal its bark. In general, however, they tend to the shady side, and are attracted toward opaque objects, furnishing an exemplification of Mr. Knight's beautiful explanation of motion in tendrils, which, by their propensity to avoid the light and approach the shade, are directed into contact with bodies capable of yielding them support.

The size of the stem in this vine is commonly not more than an inch. Sometimes, however, in very old plants, it is found several times as large. It is usually compressed on the side which adheres to the support. In favourable situations it ascends to the tops of the highest rocks and trees, and is often seen restoring to decayed trunks the verdure which they have lost. When it does not meet with an elevated prop, the plant becomes stunted in its growth, is more branched, and affects a spiral mode of growth; or falls to the ground, takes root and rises again.

The genus Rhus is placed by Linnaeus in the class Pentandria, and order Trigynia. The present species, however, is dioecious, a fact which is also true of most of the American species of Rhus which I have examined. The Rhoes belong to the Linnaean natural order Dumosae, and to the Terebintaceae of Jussieu.

The leaves of the Rhus radicans are ternate, and grow on long semicylindrical petioles. Leafets ovate or rhomboidal, acute, smooth and shining on both sides, the veins sometimes a little hairy beneath. The margin is sometimes entire and sometimes variously toothed and lobed, in the same plant. The flowers are small and greenish white. They grow in panicles or compound racemes on the sides of the new shoots, and are chiefly axillary. The barren flowers have a calyx of five erect, acute segments, and a corolla of five oblong recurved petals. Stamens erect with oblong anthers. In the centre is a rudiment of a style.

The fertile flowers, situated on a different plant, are about half the size of the preceding. The calyx and corolla are similar but more erect. They have five small, abortive stamens and a roundish germ surmounted with a short, erect style, ending in three stigmas. The berries are roundish and of a pale green colour, approaching to white.

A plant has long appeared in the Pharmacopoeias under the name of Rhus toxicodendron. Botanists are not agreed whether this plant is a separate species from the one under consideration, or whether they are varieties of the same. Linnaeus made them different with the distinction of the leaves being naked and entire in Rhus radicans, while they are pubescent and angular in Rhus toxicodendron. Michaux and Pursh, whose opportunities of observation have been more extensive, consider the two as mere local varieties; while Elliott and Nuttall still hold them to be distinct species. Among the plants which grow abundantly around Boston, I have frequently observed individual shoots from the same stock having the characters of both varieties. I have also observed that young plants of Rhus radicans frequently do not put out rooting fibres until they are several years old, and that they seem, in this respect, to be considerably influenced by the contiguity of supporting objects.

The wood of the Poison Ivy is brittle, fine grained and white, with a yellow heart in the old plants.

If a leaf or stem of this plant be broken off, a yellowish milky juice immediately exudes from the wounded extremity. After a short exposure to the air, it becomes of a deep black colour and does not again change. This juice, when applied to linen, forms one of the most perfect kinds of indelible ink. It does not fade from age. washing, or exposure to any of the common chemical agents. I have repeatedly, when in the country, marked my wristband with spots of this juice. The stain was at first faint and hardly perceptible, but in fifteen minutes it became black, and was never afterwards eradicated by washing, but continued to grow darker as long as the linen lasted.

Dr. Thomas Horsefield, in his valuable dissertation on the American species of Rhus, made various unsuccessful experiments with a view to ascertain the nature of this colouring principle, and the means of fixing it on stuffs. He found that the juice, expressed from the pounded leaves, did not produce the black colour, and that strong decoctions of the plant, impregnated with various chemical mordants, produced nothing more than a dull yellow, brownish or fawn colour. The reason of this is, that the colouring principle resides not in the sap, but in the succus proprius or peculiar juice of the plant, that this juice exists only in small quantity, and is wholly insoluble in water, a circumstance which contributes to the permanency of its colour, at the same time that it renders some other medium necessary for its solution.

With a view to ascertain the proper menstruum for this black substance, I subjected bits of cloth stained with it, to the action of various chemical agents. Water, at various temperatures assisted by soap and alkali, produced no change in its colour. Alcohol, both cold and boiling, was equally ineffectual. A portion of the cloth, digested several hours in cold ether with occasional agitation, was hardly altered in appearance. Sulphuric acid reddened the spots, but scarcely rendered them fainter. The fumes of oxymuriatic acid which bleached vegetable leaves and hits of calico in the same vessel, exerted no effect on this colour.

Boiling ether is the proper solvent of this juice. A piece of linen spotted with the Rhus was immersed in ether and placed over a lamp. As soon as the fluid boiled, the spot began to grow fainter, and in a few minutes was wholly discharged, the ether acquiring from it a dark colour. The linen at the same time became tinged throughout with a pale greyish colour, acquired from the solution.

This nigrescent juice, in common with that of the Rhus vernix, has, perhaps, claims to be considered a distinct proximate principle in vegetable chemistry.

The leaves and bark are astringent to the taste, which quality appears to be occasioned by gallic acid rather than tannin. The infusion and decoction become black on the addition of salts of iron, but discover hardly any sensibility to gelatin.

A poisonous quality exists in the juice and effluvium of this plant, like that which is found in the Rhus vernix already described. It is said, that some other species of Rhus, such as Rhus pumilum and Rhus typhinum, possess the same property in a greater or less degree. The poison Ivy, however, appears to be less frequently injurious than the poison Dogwood, and many persons can come in contact with the former with impunity, who are soon affected by the latter. I have never, in my own person, been affected by handling or chewing the Rhus radicans, though the Rhus vernix has often occasioned a slight eruption. Indeed, the former plant is so commonly diffused by road-sides and near habitations, that its ill consequences must be extremely frequent, were many individuals susceptible of its poison.

Those persons who are constitutionally liable to the influence of this poison, experience from it a train of symptoms very similar to those which result from exposure to the Rhus vernix. These consist in itching, redness and tumefaction of the affected parts, particularly of the face; succeeded by blisters, suppuration, aggravated swelling, heat, pain, and fever. When the disease is at its height, the skin becomes covered with a crust, and the swelling is so great as in many instances to close the eyes and almost obliterate the features of the face. The symptoms begin in a few hours after the exposure, and are commonly at the height on the fourth or fifth day; after which, desquamation begins to take place, and the distress, in most instances, to diminish.

Sometimes the eruption is less general, and confines itself to the part which has been exposed to contact with the poison. A gentleman, with whom I was in company, marked his wristband with the fresh juice, to observe the effect of the colour. The next day his arm was covered with an eruption from the wrist to the shoulder, but the disease did not extend further. It sometimes happens that the eruption continues for a longer time than that which has been stated, and that one set of vesications succeeds another, so as to protract the disease beyond the usual period of recovery.

The symptoms of this malady, though often highly distressing, are rarely fatal. I have nevertheless been told of cases in which death appeared to be the consequence of this poison.

The disease brought on by the different species of Rhus appears to be of an erysipelatous nature. It is to be treated by the means which resist inflammation, such as rest, low diet, and evacuations. Purging with the neutral salts is peculiarly useful, and in the case of plethoric constitutions, or where the fever and arterial excitement are very great, blood-letting has been found of service.

The extreme irritability and burning sensation may be greatly mitigated by opium. Cold applications, in the form of ice or cold water, are strongly recommended by Dr. Horsefield in his treatise, and when persevered in, they appear to exert a remarkably beneficial effect. The acetate of lead is perhaps as useful as any external palliative, and it should be used in solution rather than in the ointment, that it may be applied as cold as possible. The late Dr. Barton speaks highly of a solution of corrosive sublimate externally applied in this disease, but from trials of the two remedies made at the same time and in the same patient, I have found the lead the more beneficial of the two.

A person who has been in contact with the Rhus and finds himself poisoned, should immediately examine his hands, clothes, &c. to see if there are no spots of the juice adhering to him. These, if present, should be removed, as they will otherwise serve to keep up and extend the disorder. From a want of this precaution, the disease is frequently transferred from the hands to different parts of the body, and likewise kept up for a longer time than if the cause had been early removed. As washing does not eradicate the stains of this very adhesive juice, it is best to rub them off with some absorbent powder.

The Rhus radicans has been administered internally in certain diseases by a few practitioners in Europe and America. Dr. Horsefield, in several instances, administered a strong infusion in the dose of about a teacup full to consumptive and anasarcous patients. It appeared to act as an immediate stimulant to the stomach, producing some uneasiness in that organ, also promoting perspiration and diuresis. Some practitioners in the Middle States, we are told by the same author, have exhibited it with supposed benefit in pulmonary consumption. A French physician, Du Fresnoy, has reported seven cases of obstinate herpetic eruption, which were cured by the preparations of this plant. His attention was drawn to the subject by finding that a young man who had a dartre upon his wrist of six years' standing, was cured of it by accidentally becoming poisoned with this plant. The same physician administered the extract in several cases of palsy, four of which, he says, were cured by it.

Dr. Alders on, of Hull, in England, gave the Rhus toxicodendron in doses of half a grain, or a grain three times a day, in several cases of paralysis; and states, that all his patients recovered, to a certain degree, the use of their limbs. The first symptom of amendment was an unpleasant feeling of prickling or twitching in the paralytic limbs. Dr. Duncan, author of the Edinburgh Dispensatory, states, that he had given it in larger doses without experiencing the same success, although he thinks it not inactive as a medicine.

My own opinion is, that the plant under consideration is too uncertain and hazardous to be employed in medicine, or kept in apothecaries' shops. It is true, that not more than one person in ten is probably susceptible of poison from it. Yet, even this chance, small as it is, should deter us from employing it. In persons not constitutionally susceptible of the eruptive disease, it is probably an inert medicine, since we find that Du Fresnoy's patients sometimes carried the dose as high as an ounce of the extract, three times a day, without perceiving any effect from it.

It is true that the external application of the Rhus radicans and Rhus vernix would, in certain cases, afford a more violent external stimulus, than any medicinal substance with which we are acquainted. But since it is neither certain in its effect, nor manageable in its extent, the prospect of benefit, even in diseases like palsy and mania, is not sufficient to justify the risk of great evil.

Botanical References.

Rhus radicans, Willd. Sp. pl. i. 1481.

Elliott, i.

Rhus toxicodendron, &c. Michaux, Flor. i. 183.

Pursh, i. 205.

Toxicodendron rectum &c.

Dillenius, Elth. t. 291.

Medical References.

Du Fresnoy, quoted in Annals of Medicine, iv. 182., v. 483.

Med. and Phys. Journal, i. 308., vi. 273., x. 486.

Duncan, Dispens. 294.

Horsefield, Dissertation, Philad. 1798.

American Medical Botany, 1817-1821, was written by Jacob Bigelow, M. D.