Synonyms.—Acute Nephritis; Exudative Nephritis; Catarrhal Nephritis; Tubal Nephritis.

Synonyms.—Acute Nephritis; Exudative Nephritis; Catarrhal Nephritis; Tubal Nephritis.

Definition.—Acute inflammation of the entire structure of the kidney, varying in degree and form, and due to the action of cold or toxic agents upon the kidney.

Since every part of the kidney may be involved, writers have described a tubular, a glomerular, an interstitial, and a diffuse nephritis, while Delafield describes three varieties: (1) Acute degeneration of the. kidney; (2) Acute exudative nephritis; (3) Acute productive nephritis. These various forms, however, are only interesting in an etiological and pathological sense, and are of no practical value.

Etiology.—Acute nephritis is a disease of early life, though it may occur at any age. It is found more frequently in males than in females, owing to greater exposure in the male. The chief exciting causes are:

Cold.—Exposure to cold and dampness is perhaps the most frequent cause, particularly exposure due to a drinking spree.

Alcoholic intemperance, aside from the exposure that usually attends overindulgence, is a cause, and albuminuria is not uncommon in beer-drinkers.

The toxins from the infectious fevers, particularly scarlet fever, which usually manifests itself during convalescence, is a frequent cause. It may also follow diphtheria, typhoid fever, measles, chicken-pox, influenza, small-pox, relapsing fever, cholera, yellow fever, typhus, cerebro-spinal fever, dvsentery, tuberculosis, erysipelas, acute articular rheumatism, malaria, and more rarely syphilis.

Certain toxic drugs, such as turpentine, carbolic acid, cantharides, potassium chlorate, salicylic acid, phosphorus, lead, arsenic, mercury, iodoform, and the mineral acids.

Chronic skin-diseases and severe burns may also prove exciting causes.

Pregnancy.—It is not uncommon during- the last months of pregnancy, especially in primipara, for a nephritis to develop. This is due partly to pressure on the renal vessels by the gravid uterus, and partly to the altered blood changes.

Pathology.—The appearance of the kidneys and the anatomical changes depend upon the degree of the inflammation, the portion involved, and the stage of the disease.

While the volume of the organ is always increased, there may be no perceptible change to the naked eye where the inflammation is mild. The fibrous capsule is loosely attached, and may be easily stripped off, unless previous inflammation has resulted in firm attachments. In the more severe form, however, the organ is swollen, of a dark-red color, and when incised, the cut surfaces drip blood, and the tissue is soft and friable. The pyramids and malpighian bodies are found deeply stained, which change to a mottled appearance as the disease progresses, the anatomical changes that take place are responsible for the differentiation of the different forms of nephritis which have been given by authors, and are as follows:

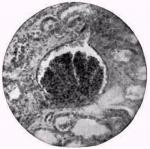

Glomeruli.—The epithelial cells of the tufts are the principal seat of the inflammation when due to the toxic effect of drugs or infectious diseases. The cells at first become swollen and granular (cloudy swelling), but later they may become irregular in form and undergo fatty or hyaline degeneration. Accompanying these changes, exudative processes are taking place in the interstitial tissue, which make the entire process a true nephritis. In some cases of scarlatina, the parenchymatous degeneration is almost entirely confined to the glomeruli, when it is termed glomerulo-nephritis.

Glomeruli.—The epithelial cells of the tufts are the principal seat of the inflammation when due to the toxic effect of drugs or infectious diseases. The cells at first become swollen and granular (cloudy swelling), but later they may become irregular in form and undergo fatty or hyaline degeneration. Accompanying these changes, exudative processes are taking place in the interstitial tissue, which make the entire process a true nephritis. In some cases of scarlatina, the parenchymatous degeneration is almost entirely confined to the glomeruli, when it is termed glomerulo-nephritis.

Changes in the Tubules.—The tubular epithelium undergoes similar changes; viz., cloudy swelling, followed by fatty and granular degeneration. This lessens the caliber of the tubule, and, as a result, the tubule becomes choked with the altered contents. The convoluted tubules contain, in addition to the changed epithelial cells, leukocytes and blood-corpuscles.

Interstitial Changes.—In nearly all cases of nephritis, an inflammatory exudate, consisting of serum, leukocytes and red

blood-corpuscles, takes place between the tubules. Later, round-cell infiltration may take place, and where this exudate becomes organized, we have a fibroid degeneration of the kidney, with permanent impairment of its function.

Symptoms.—The onset is usually sudden when due to exposure to cold, and frequently during the convalescence of scarlet fever. The patient will be seized with a chill, or chilly sensations will appear, with nausea and vomiting, and often in children a convulsion—uremic—ushers in the disease. The latter may also be the initial symptom in -he adult. Edema rapidly ensues, the eyelids and face becoming puffy within twenty-four or forty-eight hours, to be soon followed by dropsy in the ankles. The fever varies, though usually never very high, ranging from 101° to 103°. The pulse is generally hard, with increased tension and accentuation of the second cardiac sound.

The urinary symptoms are characteristic. The urine is scanty, highly colored, smoky, and contains albumin, red and white blood-corpuscles, hyaline, granular, and epithelial casts. The quantity varies from a few ounces to two pints, though in very severe cases there may be suppression. The specific gravity at first is high, 1,025 or higher, but later it falls to 1,010 or 1,015. There is a frequent desire to void water, attended with more or less tenesmus.

Anemia develops very early, and, where dropsy becomes extensive, ascites, hydrothorax and hydropericardium become prominent features, dyspnea being one of the most distressing symptoms.

The disease may come on very insidiously. The patient has but little pain, and for some time is not aware of his true condition. The skin becomes pale, and sometimes a little waxy. It is dry and constricted, there is slight headache, and the patient desires to micturate quite often, though the quantity is small. The eyelids are puffy on rising; but this disappears as the day advances. There is loss of appetite, nausea, and sometimes vomiting. Headache is a general complaint.

Gradually dropsy becomes more marked, there is more or less dyspnea, and the symptoms are those of the chronic form. The urine is small in quantity, four to six ounces, is dark red, and loaded with albumin and casts.

Diagnosis.—This will depend upon the history of the case, the general appearance of the patient, and the presence of albumin, hyaline, granular, and epithelial casts, and white and red blood-corpuscles in a highly colored urine.

Whenever a patient complains of headache, and there is pallor of the skin, puffy eyelids, muscular twitching, nausea, and vomiting, the urine should be examined.

The pregnant woman's urine should be tested occasionally, after the sixth month, especially if diminished in quantity. We are to remember, however, that we may have albumin in the urine in both pregnancy and febrile diseases, and not have nephritis; in these cases, however, there are but few casts.

Prognosis.—This depends somewhat upon the character of the inflammation and the cause giving rise to n.

When due to cold or pregnancy, the prognosis is favorable, and the duration not long. Scarlatinal nephritis is more serious, though not necessarily fatal. If the edema disappears, and the urine increases in quantity and becomes lighter in color, the case is favorable. The nephritis following or accompanying typhoid fever and diphtheria is also favorable.

Where severe, and due to phosphorus or mercurial poisoning, or when it occurs in cholera or yellow fever, the outlook is not so favorable; also when there is great dropsical effusion, the fluid involving the cavities, as in ascites, hvdrothorax, and hydropericardium.

Treatment.—The patient should be put to bed, kept between blankets, and not allowed to get up till all traces of the disease have disappeared. In the treatment of nephritis the profession seems divided as to the use of diuretics and the use of fluids; one advocating the flushing of the kidneys with various diuretics, while another will advocate the withholding of fluids, even in the way of nourishment, confining the patient to a strictly dry diet and limiting the water-supply to eight or ten ounces per day. I believe that there is a happy medium between these two extremes.

Where there is active fever, and the inflammation sthenic in character, diuretics should not be used, though water may be taken in moderate quantities. In such cases we begin our treatment with the appropriate sedative, aconite or veratrum, as the case may require, and combine with it gelsemium if the face be flushed and the patient restless, showing evidences of nervous irritation. Rhus tox. will replace the gelsemium if we have the sharp stroke of the pulse, elevated papilla on tongue, with pinched features. In the child there is sudden starting in the sleep. In such cases rhus tox. is the remedy. If there is much tenesmus, viburnum will be useful, while eryngium and apis will be called for when there is a sensation of burning in the bladder and urethra on micturition.

Echinacea will be a splendid agent, with the first evidence of uremia. As soon as the fever subsides and the acute symptoms pass off, mild and unirritating diuretics will be useful. A hot infusion of althea, verbascum, apium, polytrichum. etc., will increase the flow of urine, when the more tonic diuretics, hydrangia, agrimony, collinsonia, uva ursi, etc., will give good results.

Pilocarpin.—Where the skin is dry and harsh, with high temperature, and the pulse is full and strong, a hypodermic injection of one-eighth grain of pilocarpin will be found very beneficial.

Apocynum.—For the puffiness of the eyelids and face, and later for general dropsy, apocynum is one of our best agents.

Fowler's Solution.—For the anemic condition as shown by the pale, waxy skin and the colorless tongue, Fowler's solution ten drops, to water four ounces, a teaspoonful every hour, will be found to be beneficial. If there be hemorrhage, gallic acid in five-grain doses will bring prompt relief.

The bowels should be kept soluble during the entire course of the disease, and perspiration encouraged. Where nausea and vomiting are present, the stomach may be washed out, by having the patient drink freely of warm mustard or salt water, after which rhus tox., ipecac, nux vomica, and like remedies may be used.

The diet should be bland and unirritating, and consist mostly of milk; buttermilk or whey may also be used, as may also chicken, clam, or mutton broth. Later, gruels, the cereals, and fruits may be added, but meat and potatoes should be restricted until the patient is well in the convalescent period.

As a drink, pure water is perhaps the best, though a little cream of tartar, with lemonade and sugar, makes a good diluent drink.

The acetate and citrate of potassium and the benzoate of sodium, well diluted, render the urates less irritating, and favor their elimination, and will be found useful in the later stages.

During convalescence the child should be guarded from taking cold. Where possible, a change to a warm, sunny, and equable climate will prove highly beneficial.

The Eclectic Practice of Medicine, 1907, was written by Rolla L. Thomas, M. S., M. D.